In de marge van de canon: Over Nederlandse architectuur in de eerste architectuurgeschiedenisboeken

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.7480/knob.114.2015.1.1000##submission.downloads##

Samenvatting

The problematic relationship between, on the one hand, monographs and local and national studies and, on the other hand, general historiography is the subject of much debate nowadays. Informed by the postcolonialist theory of architecture and more recent attempts to write alternative world histories of art and architecture, the question arises how the history of architecture can provide insight into the vast diversity of our built environment. How can we develop alternatives for the stereotypical architectural canon and its persistent margins?

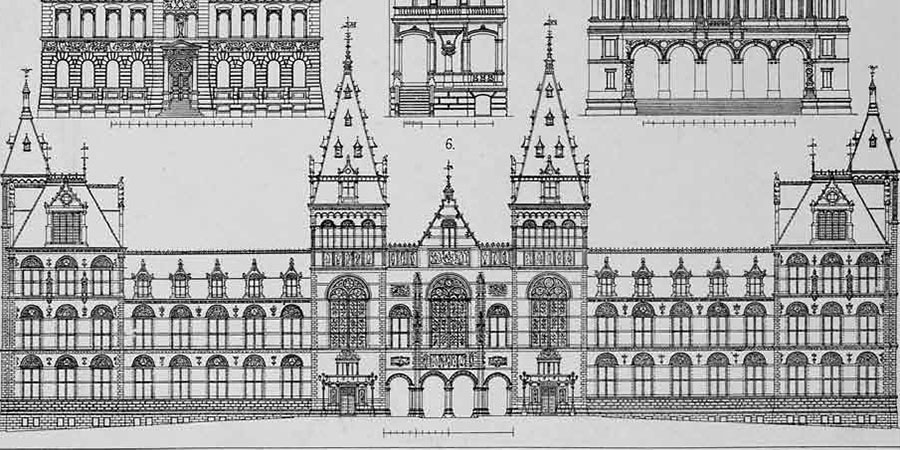

The present article explores the origins of one of those margins: the Dutch architecture of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. It describes how Dutch architecture was characterized and evaluated in the first surveys of architectural history of the 1850s: J. Fergusson, The Illustrated Handbook of Architecture: Being a Concise and Popular Account of the Different Styles of Architecture Prevailing in All Ages and Countries (1855), W. Lübke, Geschichte der Architektur. Von den ältesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart (1855); and F. Kugler’s fivevolume Geschichte der Baukunst (1856-1873).

In order to make the immense subject of the history of architecture comprehensible, Fergusson, Lübke and Kugler constructed a continuous narrative through the ages in their books. Readers would follow the progressive development of architectural styles by means of the most representative and purest examples, such as the French and German cathedrals of the Gothic era and the Italian palazzi and French castles of the Renaissance. This descriptive method reduced all other historical monuments, including the Dutch ones, to buildings that were less pure in style and therefore marginal examples of the main style.

Numerous more specific studies appeared to make marginal styles more widely known and sometimes neargued for their appreciation as well. For example, Auguste Schoy wrote in his Histoire de l’influence Italienne sur l’architecture dans les Pays-Bas (1879) that the Dutch Renaissance style ought to be judged on its own merits. According to Schoy, the influence of the Italian Renaissance on the Low Countries did not reside in formal similarities such as symmetry or the correct application of the classical orders and monumentality, but in the ornamentation. The non-monumental building in bricks that is so typical of the Low Countries was modernized by adopting Renaissance motifs from Italy in its ornamentation, which resulted in a picturesque beauty all its own.

Acknowledging these studies, the general historiographies adapted their new editions: they became more voluminous and more richly illustrated, but they did not change the main order of the history of architectural styles and their selection of most representative architectural monuments also remained the same. One of the reasons for this was that the sub-studies did not question the narrative presented by the surveying publications. Schoy too accepted the superior status of the Italian Renaissance as a given and studied its influence on the Low Countries. The result of his research amounts to no more than the fact that the Dutch Renaissance was promoted from a negatively judged position in the margin to a positive one.

This article argues that by adopting both the method and terminology of the general historiography of architecture, the more specific studies perpetuated the margins. They confirmed the narrative that Dutch architecture was an imperfect or at best fairly successful application of a style that was to be admired in its most perfect beauty elsewhere: at the most representative architectural monuments.

Referenties

J. Nasr en M. Volait, ‘Still on the margin. Reflections on the persistence of the canon in architectural history’, ABE Journal. European architecture beyond Europe 1 (2012), geraadpleegd op 5 januari 2015, dev.abejournal.eu/index?id=304. Zie ook: D.A. Levine en L. Silver, ‘“Quo vadis Hagia Sophia?” Art history’s survey texts’, CAA.reviews (25 januari 2006), online (over de canonieke kunstgeschiedenisboeken) en W.S. Saunders, Judging architectural value. A Harvard design magazine reader, Minneapolis, MN/Londen 2007 (over de beoordelingscriteria van architectuur).

Nasr en Volait 2012 (noot 1), alinea 7.

Levine en Silver 2006 (noot 1); J. Komisar, ‘Designing a better textbook. Challenges to the expansion of the content of architectural history survey text, ABE Journal. European architecture beyond Europe 1 (2012), alinea 10.

D. Baalman, ‘Nederlands eerste hoogleraar bouwkunde: Eugen Gugel’, De Sluitsteen 7 (1991) 2/3, 43-66; C.P. Krabbe, Ambacht, kunst en wetenschap. Bevordering van de bouwkunst in Nederland (1775-1880), Zwolle 1998, 154-156 en 232-235; P. Brouwer, De wetten van de bouwkunst. Nederlandse architectuurboeken in de negentiende eeuw, Rotterdam 2011, 208-209.

F. Kugler, Handbuch der Kunstgeschichte, Stuttgart 1842, x.

W. Beyrodt, ‘Kunstgeschichte als Universitätsfach’, in: P. Ganz en M. Gosebruch (red.), Kunst und Kunsttheorie 1400-1900, Wiesbaden 1991, 313-333.

Voor de ontwikkeling van de architectuurhistorische discipline zijn de studies over de auteurs informatief. R. Elwall, ‘James Fergusson (1808-1886): a pioneering architectural historian’, RSA Journal 139 (1991) 5418, 393-404. Voor Kugler: D. Karlholm, Art of illusion. The representation of art history in nineteenth century Germany and beyond, Bern 2004 en M. von Espagne, B. Savoy en C. Trautmann-Waller (red.), Franz Theodor Kugler. Deutscher Kunsthistoriker und Berliner Dichter, Berlijn 2010. Over Lübke is weinig geschreven. Zijn naam wordt meest zijdelings genoemd in de Duitse historiografische literatuur. De beste bron is Karlholm 2004. Typisch voor de negentiende eeuw waren dit soort omvattende werken ook bedoeld voor het hoog opgeleide, cultureel geïnteresseerde publiek. Alle drie auteurs noemen deze doelgroep in hun voorwoord. In het kader van dit artikel wordt hier verder niet op ingegaan.

Elwall 1991 (noot 7), 393-404.

Aan een latere bewerking en uitbreiding van Illustrated handbook of architecture, dat vanaf 1862 een nieuwe titel kreeg, A history of architecture in all countries, from the earliest times to the present day, voegde Fergusson in 1876 een apart deel toe: History of Indian and Eastern Architecture.

J. Fergusson, Illustrated handbook of architecture, Londen 1855, dl. 1, vi-vii.

Fergusson 1855 (noot 10), x.

Karlholm 2004 (noot 7), 144.

W. Lübke, Geschichte der Architektur, Leipzig 1855, 2. Volgens Lübke was er eigenlijk pas op het moment dat architectuur alle maatschappelijke behoeften vormgeeft, echt sprake van een ‘vollkomenes Spiegelbild des gesammten Charakters einer Zeit’.

Kugler 1842 (noot 5), x-xi.

Voor het belang van het idee van een volks- en tijdgeest voor de kunstgeschiedschrijving, zie: T. DaCosta Kaufmann, Toward a geography of art, Chicago/Londen 2004.

Voor een recente analyse van het negentiende-eeuwse stijlbegrip, zie: M. Hvattum, ‘Crisis and correspondence: Style in the nineteenth century’, Architectural Histories 1 (2013) 1, 1-8.

Lübke 1855 (noot 13), 35-37.

Lübke 1855 (noot 13), 4.

Fergusson 1855 (noot 10), 133.

Kugler 1842 (noot 5), 19.

I. Warnsinck, ‘Voorrede’, Bouwkundige Bijdragen 1 (1843), v; N.N., ‘Een goed plan’, De Opmerker. Bouwkundige Weekblad 29 (1894) 15 december, 393-395.

Kugler in Bouwkundige Bijdragen 1849, 287-289; Kugler in Bouwkundige Bijdragen 1851, 212.

Krabbe 1998 (noot 4), 115 en volgende.

Warnsinck 1843 (noot 21), v.

N.N. 1894 (noot 21), 393.

W. Lübke, Geschichte der Architektur, Leipzig 1886, dl. 2, 75.

J. Fergusson, A history of architecture in all countries, Londen 1874, dl. 1, 609.

A. Schayes, Histoire de l’architecture en Belgique, Brussel 1850. Schayes verwijst in zijn studie niet naar Oltmans.

C.F. von Wiebeking, Theoretisch-practische bürgerliche Baukunde, durch Geschichte und Beschreibung der merkwürdigsten Baudenkmahle und ihre genauen Abbildungen bereichert, München 1821-1826 (6 dln.). Voor Wiebekings positie in Nederland, zie: C. Bertram, Stille Grösse. Das niederländische Interesse an deutscher Architektur und Architekturförderung im 19. Jahrhundert, Rijksuniversteit Groningen 2009 (dissertatie), 52-53.

[G.R.] Hermans, ‘Geschichte des Bauens des St. Johannis-Kirche in Herzogenbusch’, in het tijdschrift Organ für christliche Kunst 4 (1854) 3, 17-23. Dit artikel, zo wordt aan het begin vermeld, is een samenvatting van een onderzoek van G.R. Hermans uit Den Bosch, over de voorgenomen restauratie van de Sint Jan. ‘‘ber einige mittelalterliche Kirchen in den Niederlanden (Holland und Belgien)’ verscheen in 14 afleveringen in Organ für christliche Kunst 6 (1856) in de nummers 1-20. Het betreft een behoorlijk omvangrijke en grondige reeks gebouwbeschrijvingen naar aanleiding van een reis die een zekere Essenwein in Nederland en België maakte. Van de belangrijkste gebouwen zijn tekeningen van plattegronden en details gemaakt.

Rudolf Redtenbacher (1840-1885) was op verzoek van de Nederlandse regering lid van het College van Rijksadviseurs (1874-1879), dat adviseerde over monumentenbeleid, en deed regelmatig verslag van het historisch onderzoek in de Romberg’sche Zeitschrift. Zie: L. von Donop, ‘Rudolf Redtenbacher’, in: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, dl. 28 (1889), 778-780 (geraadpleegd op: de.wikisource.org/w/index.php?title= ADB:Redtenbacher,_Rudolf&oldid=2138399, 21 november 2014).

F.N.M. Eyck tot Zuylichem, ‘De voormalige St. Marie-kerk te Utrecht’, Tijdschrift voor oudheden, statistiek, zeden en gewoonten, regt, genealogie en andere delen der geschiedenis van het bisdom, de provincie en de stad Utrecht. Tweede deel, Utrecht 1848, 19-32 en F.N.M. Eyck tot Zuylichem, ‘Kort overzigt van den bouwtrant der Middeleeuwsche kerken in Nederland’, Berigten van het Historisch Gezelschap te Utrecht. Tweede deel, eerste stuk, Utrecht 1849, 67-146.

F. Ewerbeck (e.a.), Die Renaissance in Belgien und Holland, Leipzig 1883; F. Ewerbeck, ‘Studien zur Geschichte der Früh-Renaissance in Holland und Belgien’, Kunstgewerbeblatt 1 (1885) 10, 177-182 en 11, 201-206; G. Galland, Die Renaissance in Holland, Berlijn 1882. Lübke 1886 (noot 26), 443 verwees ook naar een recensie van zijn boek over de Duitse renaissance van R. Redtenbacher, ‘Bücherschau. Wilhelm Lübke, Geschichte der Renaissance in Deutschland, Zeitschrift für Bildende Kunst. Kunstchronik 20 (1885), 44-49 in verband met een discussie over de introductie in de Nederlandse architectuur van Italiaanse ornamenten.

J. van Campen, Afbeelding van ‘t Stadhuys van Amsterdam, Amsterdam 1665-1669.

Zie hierover: Brouwer 2011 (noot 4), 315-318.

F. Kugler, Geschichte der Baukunst. Vierter Band. Geschichte der Neueren Baukunst von Jacob Burckhardt und Wilhelm Lübke. Erstes Buch. Die Renaissance in Italien, Stuttgart 1867; idem, Zweites Buch. Geschichte der Renaissance in Frankreich von Wilhelm Lübke, Stuttgart 1867; idem Fünfter Band. Geschichte der Deutschen Renaissance von Wilhelm Lübke, Stuttgart 1878.

Dit onderzoek was eerder als artikel verschenen in de Bouwkundige Bijdragen en met steun van de Maatschappij tot Bevordering der Bouwkunst als een zelfstandige publicatie uitgebracht. A. Oltmans, ‘Beschrijving en archaëologisch onderzoek der achthoekige en romaansche kapellen, op het Valkhof te Nijmegen’, Bouwkundige Bijdragen (1845) derde deel, 297-342 en Bouwkundige Bijdragen (1847), 23-42; 185-192.

J. Fergusson, History of architecture in all countries. From the earliest times to the present day, New York [1883].

In de jaren zestig en zeventig kwam Fergusson met de meest ingrijpende verandering. De twee kerndelen van History of architecture in all countries. From the earliest times to the present day, Londen 1865-1867 bouwden voort op zijn handboek uit 1855, maar de hoofdstukken over de nieuwste tijd, beginnend met de renaissance en die over India en Azië, werden zelfstandige delen: History of the modern styles of architecture: being a sequel to the Handbook of architecture (Londen 1862) en History of Indian and Eastern Architecture (Londen 1876).

Fergusson, Illustrated handbook of architecture 1855, dl. 2, 564-565; Lübke 1855 (noot 13), 154; F. Kugler, Geschichte der Baukunst, Stuttgart 1856, dl. 1, 409.

Fergusson 1855 (noot 40), 607-609.

F. Kugler, Geschichte der Baukunst, Stuttgart 1859, dl. 3, 419-427 had wel een klein hoofdstukje over de profaanbouw in België, maar niet over die in Nederland.

E. Gugel, Geschiedenis van de bouwstijlen in de hoofdtijdperken der architectuur, Arnhem 1869, 437, 445.

Gugel 1869 (noot 43), 475-476. Kenmerkend voor de gotische woonhuizen waren hun uiterst onregelmatige plattegronden, en dat was ook aan de gevel van het Gemeenlandhuis te zien, dat met zijn verspringende ramen en ingang aan de zijkant van het huis de ongelijke liggingen en hoogte van de vertrekken weerspiegelde.

Kugler 1859 (noot 42), 427-435. Vgl. Lübke 1886 (noot 26), 78-88. In de eerste druk van Lübke uit 1855, is er nog geen vermelding van de romaanse of gotische architectuur in Nederland.

Fergusson 1862, 373-374.

Gugel 1869 (noot 43), 547-550.

Lübke 1855 (noot 13), 373.

Lübke 1886 (noot 26), 443.

Lübke 1886 (noot 26), 932.

E. Gugel, Geschiedenis der bouwstijlen in de hoofdtijdperken der architectuur, Arnhem 1886, 797-799.

Lübke 1886 (noot 26), 452.

Gugel 1886 (noot 51), 806-807. Gugel meende dat ‘de bouwkundige détails [van het Leidse raadhuis] geene door strenge studie geoefende hand verraden’, in tegenstelling tot de Haarlemse Vleeshal, waarvan het ontwerp getuigde van een ‘vaste meesterhand’.

Kugler 1842 (noot 5), xi.

Kugler 1859 (noot 42).

Zie bijvoorbeeld Lübke 1886 (noot 26), inhoudsopgave.

Brouwer 2011 (noot 4), 313-318.

Oltmans 1847 (noot 37), vi.

Organ für christliche Kunst 1856 (noot 30), afl. 1, 2. Omdat het artikel geen zelfstandige, systematische geschiedschrijving beoogde, bood het de informatie aan in de vorm van een reisverslag. ‘Folgen wir also im Geiste noch einmal Stadt für Stadt den Erscheinungen, die sich auf der Reise uns dargeboten.’ Van deze reiservaring was uiteraard niets terug te vinden in de informatie die Kugler in Geschichte der Baukunst overnam.

A.W. Weissman, Geschiedenis der Nederlandsche bouwkunst, Amsterdam 1912, 437.

S. Kostof, A history of architecture. Setting and rituals, New York/Oxford 1995 (2e druk van 1985); M. Trachtenberg en I. Hyman, Architecture. From prehistory to postmodernity, New York/Upper Saddle River 2002 (2e druk van 1986); D. Watkin, A history of western architecture, Londen 2005 (4e druk van 1986).

Voor een postkolonialistische, nationale architectuurgeschiedenis, zie bijvoorbeeld T.Guha-Tharkurta, Monuments, objects, histories. Institutions of art in colonial and post-colonial India, Delhi 2004.

F.D.K. Ching (e.a.), A global history of architecture, Hoboken 2011, xi-xii.

Nasr en Volait 2012 (noot 1), alinea 10 en 16 en Komisar 2012 (noot 3), alinea 9.

Gepubliceerd

Citeerhulp

Nummer

Sectie

Artikelen

Licentie

Copyright (c) 2015 Petra Brouwer

Dit werk wordt verdeeld onder een Naamsvermelding 4.0 Internationaal licentie.