Plastic dreams

Facades of fibre-reinforced plastic (FRP) in the Netherlands

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.48003/knob.122.2023.4.808Downloads

Abstract

In the wake of the Second World War, architects and construction companies in the Netherlands started to experiment with the use of fibre-reinforced plastic (FRP) in architecture. At the time this combination of polyester and fibreglass, which is strong, malleable and lightweight, was seen as an ideal building material. Yet to date very little research has been carried out into the use of FRP in Dutch architecture. This article investigates the social changes that prompted architects and construction companies to experiment with FRP.

After the Second World War various factories in the transport industry were keen to find new markets for their expertise with FRP. They found them in housing construction. The plastic material was eminently suited to system building, a process that speeded up the construction of much-needed housing. Thanks to its high load-bearing capacity and factory production, FRP was ideal for the sandwich panels used in this construction method.

Another factor in FRP’s favour was the prevailing sense of optimism about the future in the Netherlands in that period. Architects were considering new, flexible forms of living and the designs they produced gave residents the freedom to organize, extend and even relocate their dwelling. Some architects also felt that the outward appearance of buildings should change – that a new era demanded new forms. Buildings should express an optimistic view of the future, and for that FRP, which could be produced in a wide range of shapes and colours, was ideal. Until 1973, that is, when the global oil crisis caused the price of oil to rise so steeply that the use of FRP in large-scale housing projects ceased to be cost-effective.

Many of the buildings containing FRP have since been demolished. The earliest examples were often experimental prototypes, one-off structures not intended for long-term occupancy. Plastic never became really popular as a building material for housing; people were reluctant to exchange their solid brick or concrete dwellings for a plastic version.

Fast forward to today and the restoration and preservation of buildings constructed with FRP is problematical since the relevant expertise is still lacking in the heritage sector. Nonetheless, interest in plastic architecture is growing, accompanied by an emphasis on preservation rather than demolition. This new approach is a corollary of the increasing interest in post-1965 architecture. The negative image of FRP is gradually starting to change.

References

S.C. Rasmussen, ‘From Parkesine to celluloid. The birth of organic plastics’, Angewandte Chemie (International ed.) 60 (2021) 15, 8012-8016. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202015095

I. ter Borch e.a., Skins for buildings. The architect’s materials sample book, Amsterdam 2004, 430. Zie ook: P. Voigt, Die Pionierphase des Bauens mit glasfaserverstärkten Kunststoffen (GFK) 1942 bis 1980, proefschrift Bauhaus-Universität Weimar, 2007, 39; E. Genzel en P. Voigt, ‘Plastik-Träume’, Tec21 132 (2006) 44, 4.

P. Huybers, ‘Het kunststof huis’, de Architect 6 (1975) 7, 27-31.

Geschreven bronnen zijn onder meer: E.K.H. Wulkan, ‘Experimentele woonhuizen van kunststof II’, Bouw 18 (1963) 51, 1762-1767; ‘Heeft een plastichuis toekomst?’, Plastica. Maandblad ter verspreiding van de kennis der kuststoffen 9 (1956) 8, 456-459; ‘Kunststoffen voor de woningbouw’, Algemeen Handelsblad, 13 april 1966, 4; L. van Zetten, Kunststoffen in de bouw, Doetinchem 1971, overdruk van de artikelenserie ‘Kunststoffen in de bouw’, verschenen in Bouwwereld van 9 en 23 mei, 6 en 20 juni, 4 en 18 juli 1969; E.M.L. Bervoets en F.C.A. Veraart met medewerking van M.Th. Wilmink, ‘Bezinning, ordening en afstemming 1940-1970’, in: J.W. Schot e.a. (red.), Techniek in Nederland in de twintigste eeuw. Deel 6: Stad, bouw, industriële productie, Zutphen, 2003, 215-239.

Rasmussen 2021 (noot 1); P. Bot, Vademecum: Historische bouwmaterialen, installaties en infrastructuur, Alphen aan de Maas 2009, 176.

Y. Shashoua, Conservation of Plastics. Materials science, degradation and preservation, Oxford 2008, 31.

Bot 2009 (noot 5).

J.F Kohlwey, Kunststoffen. Fabricage, eigenschappen, verwerking, toepassing, Amsterdam 1971, 166-172. Zie ook: E.A.H. Algra, ‘De afdeling G.K.: Gewapende kunststoffen’, Plastica. Maandblad ter verspreiding van de kennis der kunststoffen 9 (september 1956) 9, 512-516; en A. Faas, Praktijk-handboek kunststoffen: koudhardend – glasvezelgewapend, Baarn 1991, hfst. 1.

Genzel en Voigt 2006 (noot 2), 4-9.

J. Schepers, Wonen in kunststof. N.V. Koninklijke Nederlandse Vliegtuigenfabriek Fokker, 1958-1975, Schalkhaar 2012, 28-29.

Faas 1991 (noot 8), hfst. 1; Genzel en Voigt 2006 (noot 2).

Voigt 2007 (noot 2), 12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4171/dm/227

Schepers 2012 (noot 10), 21.

Ter Borch 2004 (noot 2), 431.

Shashoua 2008 (noot 6), 31.

A. Koch, Plastic aangeprezen. Het imago van kunststof in de wooncultuur van de laatste vijftig jaar, Zoetermeer 2003, 13.

Heeft een plastichuis toekomst? 1956 (noot 4), 456-459 en ‘Heeft een plastichuis toekomst? Deel 2’, Plastica. Maandblad ter verspreiding van de kennis der kunststoffen 9 (1956) 9, 524-527.

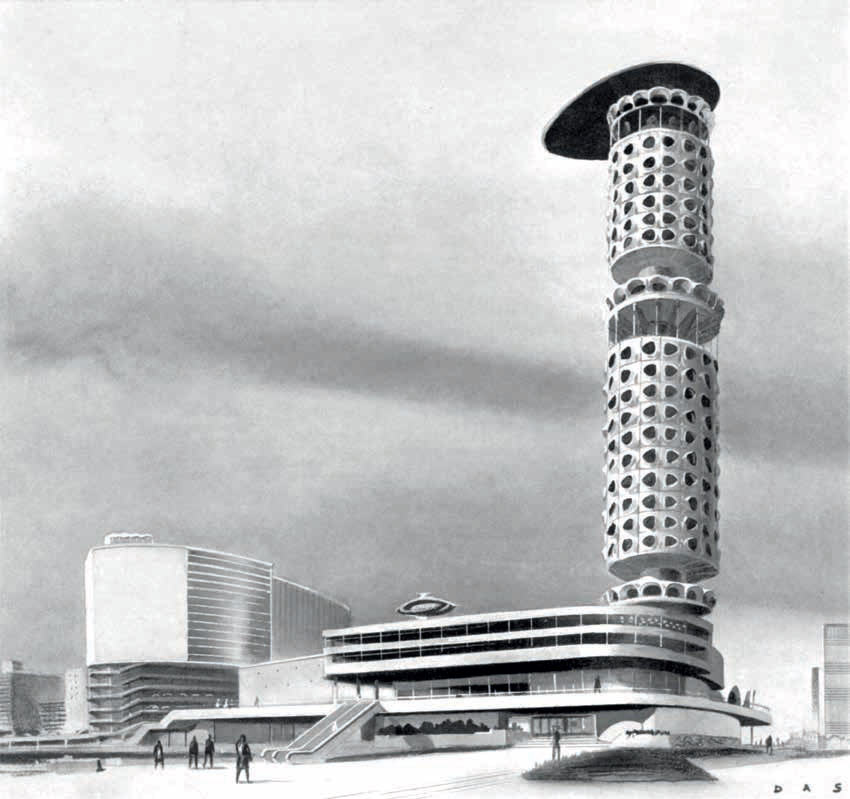

‘Hotel voor jaar 2000 ontworpen’, Het Parool, 12 mei 1966, 3.

R. Das, R. Das en C.R. de Vries, Futurotel. De hotelkamer van de toekomst, Amsterdam 1966, citaat op de (ongenummerde) vijfde pagina.

‘Dorp in plastic’, De Tijd, 11 juli 1957, 1.

‘Na drie jaar experimenteren. Huizen van plastic. Vondst van Rotterdams architect’, de Volkskrant, 4 april 1959, 13. Zie ook: ‘Plastic bungalow lijkt op luxe bonbondoos’, Het Vrije Volk, 24 maart 1959, 7.

Wulkan 1963 (noot 4), 1765.

Plastic bungalow 1959 (noot 21), 7.

Schepers 2012 (noot 10), 11-12, 35. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0958-2118(12)70213-6

‘Bewoners loven plastic huis: vrijwel geen onderhoud en makkelijk verplaatsbaar’, Het Parool, 13 juni 1964, 3.

Schepers 2012 (noot 10), 31, 35-38. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quip.2012.01.011

Schepers 2012 (noot 10), 35-40, 59. Zie ook: Bewoners loven plastic huis 1964 (noot 25), 3; en E.K.H. Wulkan, ‘Experimentele woonhuizen van kunststof’, in: E.K.H. Wulkan (red.), Kunststoffen en bouwtechniek, Rotterdam 1970, 647-648.

‘Fokker bouwt huis van plastic’, Het Parool, 24 januari 1964, 3.

Schepers 2012 (noot 10), 31.

‘Huizen van plastic zijn in opmars’, Het Parool, 9 april 1968.

‘Polyester woningen in gebruik’, Algemeen Handelsblad, 18 november 1967, 4.

Polyester woningen 1967 (noot 31).

‘Woningen van polyester’, Algemeen Handelsblad, 6 april 1967, 9. Zie ook: Polyester woningen 1967 (noot 31).

‘Nog geen aftrek voor woningen van kunststof’, Trouw, 10 december 1968, 5.

‘Plastic-huizen-bouwer Pieter Oegema: “Je kunt er best een sigaret opsteken zonder dat er een bobbeltje in komt”’, Tubantia, 8 januari 1971, 7.

‘“Halve meloen” aan Friesestraatweg’, Nieuwsblad van het Noorden, 30 oktober 1970, 5.

Huybers 1975 (noot 3), 27-31. Zie ook: Halve meloen 1970 (noot 36), 5. Zie ook: Plastic-huizen-bouwer 1971 (noot 35), 7.

‘Wie levert welke kunststoffen in de bouw?’, Patrimonium 94 (januari 1983) 1, 27.

‘Vliegende schotel’, Het Parool, 18 september 1972, 7.

Dit is bijvoorbeeld te zien in de afbeelding die in een special van de Architect uit 1975 over kunststoffen in de bouw is geplaatst op p. 29: Huybers 1975 (noot 3), 27-31.

Vliegende schotel 1972 (noot 39), 7.

Huybers 1975 (noot 3), 27-31.

‘Kunststof-bungalow van werf’, De Tijd. Dagblad voor Nederland, 6 april 1972, 13.

‘Kunststoffen huis trekt veel bekijks’, Trouw, 6 mei 1972.

Kunststoffen huis 1972 (noot 44).

‘Gemini in Vianen’, Het Parool, 18 september 1972, 7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/953363.953365

Kunststoffen huis 1972 (noot 44).

J.F.M. Kees, ‘Kantoorgebouw te Heerlen’, Bouw 20 (1972) 26, 902-903.

E. Hollman, ‘Een nieuw leven voor de tieten van Berta?’, Zuiderlucht 2 (2008) 8, 10-11. Zie ook: C.J.W. Groot, ‘Gevelelementen van glasvezelpolyester’, de Architect 6 (1975) 7, 33-37.

Hollman 2008 (noot 49), 10-11. Zie ook: Rijckheyt, Centrum voor Regionale Geschiedenis, Heerlen. Toegang 507 Collectie Bisscheroux.

J. Niesten, ‘Van polyester naar polycarbonaat. De lange weg naar industrieel vervaardigd gevelelement’, de Architect 19 (1988) 2, 95-101.

M. Eekhout, ‘Sandwichplaten en architectuur’, in: Sandwichpanelen, symposium van de TU Delft op 1 december 1993, 1-16, 1-18.

Eekhout 1993 (noot 52). Zie ook: M. Eekhout, The making of architecture. Afscheid van prof. Ir. Jan Brouwer 17 november 2000, Den Haag, 2000, 6-7.

Architectenbureau J. Brouwer N.V., ‘Distributiecentrum in Vianen’, Bouw 27 (1972) 20, 713.

Bouwcentrum, ‘Gevelelementen van kunststof: rapport no. 4785’, Rotterdam 1975, 110; ‘Kunststofgevel in Zwijndrecht’, Plastica 30 (1977) 5, 136; ‘SBC-Verwaltungsgebäude in Zwijndrecht, Niederlande’, Bauen + Wohnen 32 (1978) 11, 437.

J.-W. Schneider, ‘Nieuw gemeentelijk monument: het voormalige SBC-kantoorgebouw’, De Brug 13 (2018) 33, 3.

P. Koster, ‘“Foeilelijk” gebouw plots monument’, AD de Dordtenaar, 20 juni 2018, 2. Zie ook: Schneider 2018 (noot 56), 3.

Huybers 1975 (noot 3), 27-31. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1108/eb053728

Bewoners loven 1964 (noot 25); Kunststoffen huis 1972 (noot 44).

Voigt 2007 (noot 2), 7.

Koster 2018 (noot 57), 2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kex424

Vereniging Hendrick de Keyser, ‘De Shelter Kor Aldershoff – lange versie’, geraadpleegd 27 juli 2023, www.youtube.com/watch?v=xag9BnAYVSs&t=2s.

Vereniging Hendrick de Keyser 2023 (noot 62).

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

Articles

License

Copyright (c) 2023 Sara Duisters

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.