Between concept and history. An analysis of the restoration of the Royal Palace (2005-2011)

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.7480/knob.112.2013.2.623Downloads

Abstract

The Royal Palace in Amsterdam (originally the town hall) was restored during 2005-2011. The restoration work was qualified as a state secret, which means that many architectural historical data are still not publicly available and that the local Department of Monuments of the city of Amsterdam does not have access to them either.

The restoration consisted of several elements.

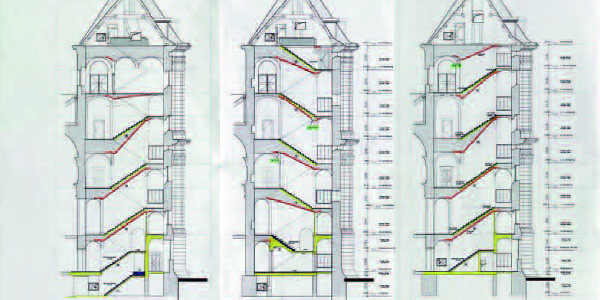

1. The renovation of the palace and its technical systems. In 2006, one third of the Imperial staircase was removed to make room for a lift. This had a severe impact on the monumental value of the staircase and it received a lot of attention in the national media, with many arguing that the staircase should be saved.

2. Initially, no funds were available for restoring the monumental interiors on the first floor of the palace. After demolishing the staircase, additional funds were finally made available to work on the interior. The aim of the restoration architect was to recreate a palace atmosphere within the context of the 17th-century town hall. This was achieved by bringing back the interior atmosphere as it had been until the previous restoration of the twentieth century. This was done mainly through soft furnishings. Also, research was done into the paintwork of the rooms, especially with regard to the 17th-century colours. The assumption here was that all wooden elements in all of the rooms (coverts, doors, coffered ceilings) had been painted in the same colour, which meant that the colour of a cupboard in the Secretary was applied to the coffered ceiling of the Thesaurie Ordinaris. This ignored the accepted principle, which was also applied in the town hall, that distinctions in venerability between the different city boards had distinctive expressions in the architecture. This principle is evident from the mantelpieces: the most important board rooms had Corinthian mantelpieces, with the exception of the Burgomaster (the most important position) whose room had a mantelpiece of all white marble, whereas the Schepenen (the aldermen) had a mantelpiece in white and red marble.

During the last restoration the doors that were reconstructed in the 20th century were kept in their redbrown colour, while the ceilings were painted in a colour that was well-intended, but most likely not original. As a result, the original architectural elements and the reconstructed ones no longer have the same colour, while this was the case in the 17th-century. The architectural concept of the 1960-1968 restoration was architecturally more coherent.

3. The natural stone on the façades of the palace was most expertly repaired. In collaboration between the restoration architect and various government departments dealing with monuments it was decided to restore the tympanum on the front to its previous glory. The architect’s aim was to take the original concept by Jacob van Campen as a starting point: light façades with windows manifesting themselves as dark recesses. However, in carrying out the work it was decided to respect the ageing of the façades, while on the other hand the historical colour of the windows was ignored. These 20th-century windows had always been white, but were now painted brown, like the 17th-century windows that were removed in 1808. This begs the question of whether the desired contrast between façades and windows was achieved.

In the end, both the exterior and the interior have become the result of opinions that were based on the personal views of those involved rather than on a historical evaluation of the palace as it stood until 2005. Another important conclusion that may be drawn from this restoration is one that concerns process. The Rgd’s (Government’s Buildings Agency) principle to declare a restoration to be confidential in order to control the process, is wrong. A top monument such as the Royal Palace requires a careful, transparent process in which citizens are informed and restoration architects, those involved in the preservation of monuments and architectural historians can freely debate various plans. That such a debate can lead to positive results is evident from the façades.

References

Met dank aan Esther Agricola, Danielle Klinkert, Coert Peter Krabbe, Vincent van Rossem, Hans Vlaardingerbroek, J. Vlaardingerbroek en Han van der Zanden voor het kritisch lezen van eerdere versies van dit artikel.

Over de trap, zie bijvoorbeeld: L. de Fauwe, ‘Trappen paleis voor lift gesloopt’, Het Parool, 22 april 2006, 1, 3; ‘Beatrix laat monumentale trap slopen’, Eindhovens Dagblad, 24 april 2006, 1; ‘Paleistrap weg’, NRC Handelsblad, 24 april 2006, 1, 9; ‘“Sloop trap paleis te dol.” Leden stadsdeelraad roepen koningin op van dienstlift af te zien’, Het Parool, 24 april 2006; L. de Fauwe, ‘“Zo speciaal is die trap ook niet.” Heel Amsterdam bemoeit zich inmiddels met de monumentale trap in het paleis op de Dam, maar slechts weinigen mochten hem ooit aanschouwen. En nu er mogelijk een lift voor in de plaats komt, is de trap opgeklommen tot staatsgeheim’, Het Parool, 25 april 2006; K. Jansen, ‘Verniel geen monument’, NRC Handelsblad, 28 april 2006, Cultureel Supplement, 2; L.Q. Onderwater, ‘Laat Paleis op de Dam toch met rust, Beatrix. De koningin laat een monumentale trap slopen’, NRC Next, 3 mei 2006; ‘Ons koningshuis voor een paleistrap!’, Het Parool, 29 april 2006, 27; G. den Aantrekker, ‘Beatrix sloopt eigen erfgoed!’, Story (16 mei 2006) 19, 22; M.J. Bok, ‘De sloop van de keizerlijke trap van het voormalige stadhuis op de Dam’, Maandblad Amstelodamum 93 (2006) 3, 3-10.

Over de gevels: T. Damen, ‘Verven of niet?’, Het Parool, 27 mei 2009, 1; T. Damen, ‘Renovatie beschadigt paleis opnieuw’, Het Parool, 27 mei 2009, 3; ‘Een geblondeerd monument voor de koningin’, NRC Handelsblad, 28 mei 2009, 6; L. van Nierop, ‘Het Paleis wordt blond. Critici noemen verfplan Paleis op de Dam een modegril’, NRC Next, 28 mei 2009, 8-9; ‘De gevel wordt blond, maar de vraag is hoe’, De Volkskrant, 29 mei 2009, 2; T. Damen, ‘Als je het Paleis schoonmaakt, kan het stuk’, Het Parool, 4 juni 2009, 16-17; T. Damen, ‘“Blijf af van gevels paleis op de Dam.” Deskundigen hekelen besluit pand te reinigen’, Het Parool, 11 juli 2009; M. van Dijk, ‘Paleis op de Dam is weer koninklijk’, Trouw, 13 juni 2009; W.van Bennekom, ‘Reiniging en herstel van de buitengevels van het Koninklijk Paleis op de Dam. Verslag van het colloquium op 19 januari 2011’, Maandblad Amstelodamum 98 (2011) 1, 7-17.

Op de op 1 augustus 2002 ingediende aanvraag tot verwijdering van asbest werd op 5 augustus 2002 positief beschikt door het stadsdeel Amsterdam-Centrum.

Vriendelijke mededeling Hans Mol, lange tijd werkzaam bij de Rgd als verantwoordelijk restauratiearchitect bij de afdeling Architecten en Advies.

J. Huisman, ‘Koninklijk Paleis wordt up to date gebracht’, Smaak. Blad voor de Rijkshuisvesting 4 (2004) 19, 42-45.

De auteur had alleen de beschikking over: Stichting Restauratie Atelier Limburg (SRAL), Vooronderzoek interieurafwerking Burgerzaal, galerijen en vertrekken eerste verdieping van het Koninklijk Paleis te Amsterdam, ongepubliceerd rapport, 2 dl., Maastricht 2003.

P.F. Vlaardingerbroek, Het stadhuis van Amsterdam. De bouw van het stadhuis, de verbouwing tot Koninklijk Paleis en de restauratie, proefschrift Universiteit Utrecht, Utrecht 2004. In gewijzigde vorm uitgegeven als P. Vlaardingerbroek, Het paleis van de Republiek. Geschiedenis van het stadhuis van Amsterdam, Zwolle 2011.

Rijksgebouwendienst (Rgd) aan Rijksdienst voor de Monumentenzorg (RDMZ), Den Haag 9 juni 2005, kenmerk KPA/trappenhuis Z-O.

Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed (RCE), pandsdossiers Koninklijk Paleis Amsterdam, Rijksdienst voor de Monumentenzorg aan het Dagelijks Bestuur van het Stadsdeel Amsterdam-Centrum, Zeist 31 mei 2005, kenmerk RW-2005-940.

Vlaardingerbroek 2011 (noot 7), 234.

J. Huisman, ‘Het paleis is nu vrij van asbest’, Smaak. Blad voor de Rijkshuisvesting 6 (2006) 27, 18-19.

P. van der Heiden, Restauratie en renovatie van het paleis. Negentiende-eeuwse schittering in zeventiende-eeuwse context, uitgave Rgd, Den Haag 2009. Met betrekking tot de interieurwerkzaamheden is zeer weinig openbaar materiaal beschikbaar: in de archieven van Bureau Monumenten & Archeologie is daaromtrent weinig tot geen informatie aanwezig.

Citaat uit Van der Heiden 2009 (noot 12), 2; voor een zeer vergelijkbare uitspraak van Krijn van den Ende, zie F. van de Poll, ‘Het paleis mag weer gewoon paleis zijn’, Smaak. Blad voor de Rijkshuisvesting 9 (2009) 42, 14-17.

Vlaardingerbroek 2011 (noot 7), 240-241.

SRAL 2003 (noot 6), 51. Of aan de kamer in een later stadium meer kleuronderzoek is verricht, is mij onbekend vanwege het feit dat het kleuronderzoek eveneens confidentieel was verklaard.

Vlaardingerbroek 2011 (noot 7), 137-138.

‘Paleis op de Dam wordt weer crème’, Smaak. Blad voor de Rijkshuisvesting 8 (2008) 37, 4; F. van de Poll, ‘Het paleis zoals het er in de zeventiende eeuw uitzag’, Smaak. Blad voor de Rijkshuisvesting 8 (2008) 38, 12-14. Na de vele openbare discussies (zie noot 2) was de toon van de titels sterk gewijzigd, zoals blijkt uit J. Huisman, ‘Contrasten in gevel paleis verzacht’, Smaak. Blad voor de Rijkshuisvesting 9 (2009) 44, 20-21.

K. van den Ende en B. van Bommel, ‘De gevels van het Koninklijk Paleis Amsterdam. Essay over het voorgestelde herstel van de belevingswaarde’, Praktijkreeks Cultureel Erfgoed 4 (2008) 13, 34.

Van den Ende en Van Bommel 2008 (noot 18), 13.

P. Vlaardingerbroek, ‘Ongeverfde natuursteen als uitdrukking van een ideaal. De gevels van het Paleis op de Dam historisch benaderd’, Amstelodamum 95 (2008) 5, 3-12.

Van den Ende en Van Bommel 2008 (noot 18), 43.

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

Articles

License

Copyright (c) 2013 Bulletin KNOB

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.