Sandstone as an architectural expression. Architectural-historical research at the Royal Palace

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.7480/knob.112.2013.2.619Downloads

Abstract

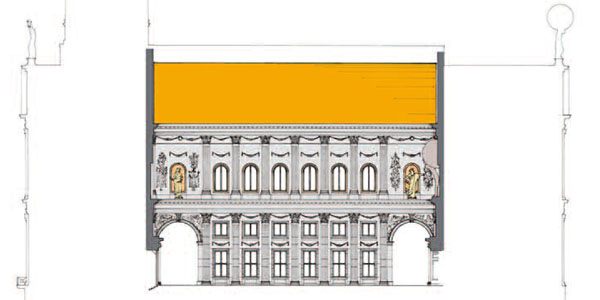

Over the past few years (2006-2011), the former town hall of Amsterdam, which has been in use as Royal Palace since 1808, was restored. During the restoration work studies of both the building history and of the colour history were conducted. This research has yielded important information about the original colour scheme of the interior and has led to the conclusion that sandstone, specifically its colour, was an important element in the architectural expression. The atmosphere of the current interior of the Royal Palace is now defined by alterations made in the early 19th century and a number of restorations carried out in the 20th century. Especially on the first floor this means that the original finish in sandstone colour is all but gone. By contrast, on the ground floor the use of sandstone as part of the original finish has been preserved in general. The sandstone, now partly painted white, was originally unpainted, as is evident from the very finely chiselled finish.

The research has also shown that some rooms on the first floor, such as the Oudraadzaal, the Mozeszaal, the Schepenkamer and the former town clerk’s office have brick vaults that were originally finished in sandstone colour. It was also concluded that the massive sandstone vaults of the galleries were originally also unpainted.

This original colour scheme contrasts with the current white appearance of the vaults on the first floor. The original interior finish was preserved best in the Rekenkamer. This room is not vaulted but has a coffered oak ceiling. The blond-brown colour scheme of this ceiling is in harmony with the yellow-grey sandstone elements of the interior. One cannot help but notice that this light colour of the ceiling differs from the other coffered ceilings on the first floor. Research has shown that the darker colour of the other coffered ceilings is a result of a restoration approach of the 20th century. The primary blonde-brown colour of the coffered ceilings was originally also in harmony with the sandstone-coloured vaults in the other rooms on the first floor.

As the town hall was converted to Royal Palace in the beginning of the 19th century, followed by a number of restorations in the 20th century, the original colour scheme of the interior had all but disappeared and with it the knowledge of these elements.

References

De voordracht van K. van den Ende over het kleuronderzoek in het Paleis op de Dam ter gelegenheid van het emeritaat van A. van Grevenstein vormde de aanleiding tot het schrijven van dit artikel.

Het kleurhistorisch onderzoek werd uitgevoerd door de Stichting Restauratieatelier Limburg (SRAL) en het bouwhistorisch onderzoek door de auteur.

N.H. van der Woude, Samenvatting stand van zaken kleurhistorisch onderzoek KPA, rapport, Amsterdam 2007. H.F.G. Hundertmark, ’t achtste wonderstuk. De bouwgeschiedenis van het stadhuis van Amsterdam, rapport, Oss 2012.

Op de begane grond bevinden zich in het totaal twaalf voormalige cellen (ook wel boeien genaamd), waarin verdachten werden ondergebracht. De vier vroegere gijzelkamers waren bestemd voor personen in schoutsgijzeling of civiele gijzeling.

Jacob van Campen had voor het ontwerp van de vierschaar twee varianten gemaakt. Bij het eerste variant is er sprake van een onbeschilderd tongewelf, bij de tweede is het gewelf voorzien van een rijke beschildering. Uiteindelijk werd gekozen voor een in massief Avender steen uitgevoerd tongewelf. Dat het inderdaad Avender steen betrof, wordt vermeld in: O. Dapper, Historische beschryving der stadt Amsterdam, Amsterdam 1663, 347.

M. van Eikema Hommes en E. Froment, ‘Het decoratie-programma in de galerijen van het Koninklijk Paleis Amsterdam: een harmonieuze interactie tussen schilderkunst, architectuur en licht?’, in: M. van der Zwaag, Opstand als opdracht. Flinck, Ovens, Lievens, Jordaens, De Groot, Bol en Rembrandt in het paleis, Amsterdam 2011, 34-53. Hundertmark 2012 (noot 2), 130-136.

Van Eikema Hommes en Froment 2011 (noot 5), 48.

Van Eikema Hommes en Froment 2011 (noot 5), 48.

Van Eikema Hommes en Froment 2011 (noot 5), 50.

Van Eikema Hommes en Froment 2011 (noot 5), 50.

P. Vlaardingerbroek, Het paleis van de Republiek. Geschiedenis van het stadhuis van Amsterdam, Zwolle 2011, 158.

Hundertmark 2012 (noot 2), 124-129.

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

Articles

License

Copyright (c) 2013 Bulletin KNOB

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.